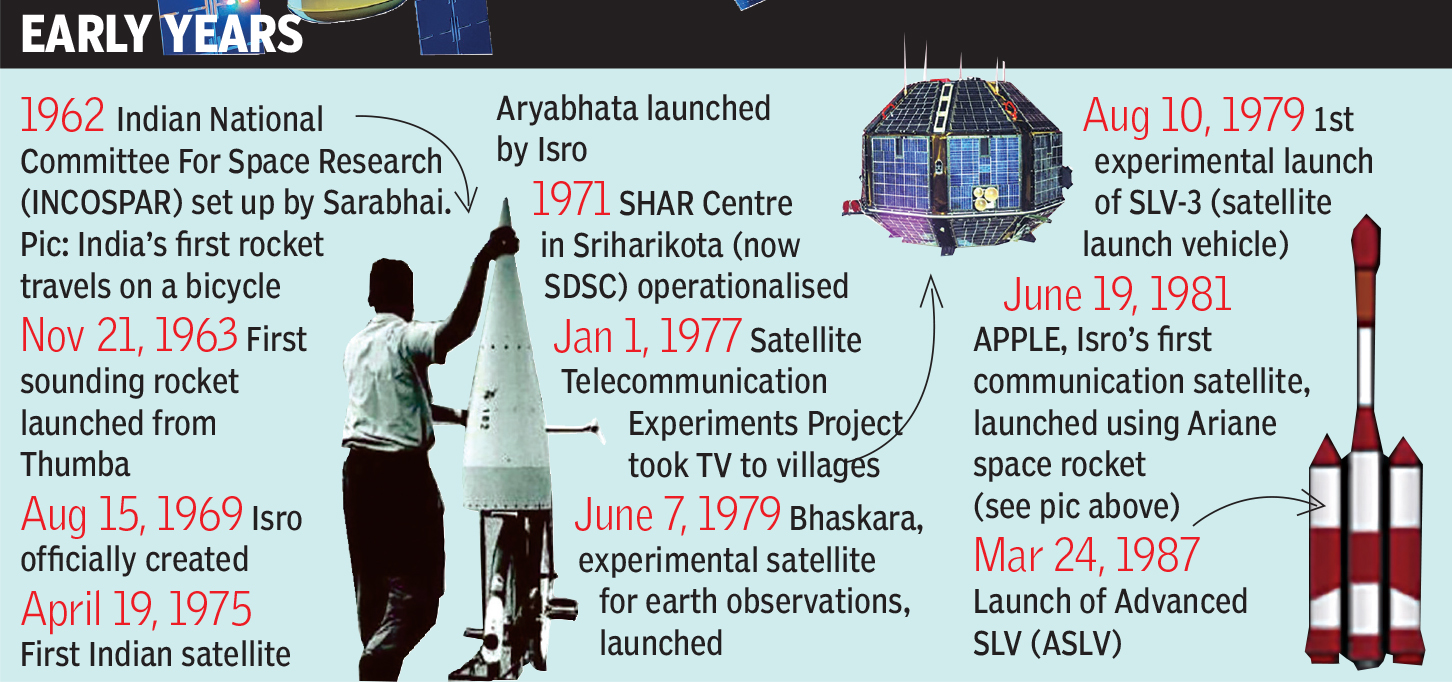

From humble beginnings, India's space programme, a story of vision, indigenisation, austerity and success, is now on the cusp of evolution. The next 10 years, pegged as a decade of space globally, is set to be cho-a-bloc with Indian milestones

On October 18, 2021, Isro performed a collision avoidance manoeuvre in a lunar orbit to prevent the Chandrayaan-2 orbiter from crashing into Nasa’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. That such a manoeuvre was required around the Moon — where the number of objects is very low unlike the hundreds in the Low Earth Orbit —surprised many. But it was a matter of pride for India that among the very few spacecraft there was one it had launched.

Notwithstanding the failure to soft-land the lander, Chandrayaan-2 was indicative of India’s capabilities. From humble beginnings at a church, India’s space programme now boasts one of the largest fleets of communication and remote sensing satellites, application-specific satellite products and tools — for broadcast, communication, weather forecast, disaster management, GIS, cartography, navigation, telemedicine, distance education — two largely successful class of launch vehicles (PSLV & GSLV), Moon and Mars missions...

The space programme is undoubtedly among the brightest stars in the constellation of India’s feats in science. That this was achieved on shoestring budgets incomparable with big space faring nations makes the success sweeter: recall the famous comparison of the Mars Orbiter Mission (MOM) costing less than a Hollywood flick.

India’s overall space expenditure in 2019 was $1.8 billion, 10 times less than the US ($19.5 billion) and six times less than China ($11 billion). In 2022, India’s space programme will complete 60 years, and, from being synonymous with the government, it’s opening up to enable private enterprises to participate in end-to-end activities.

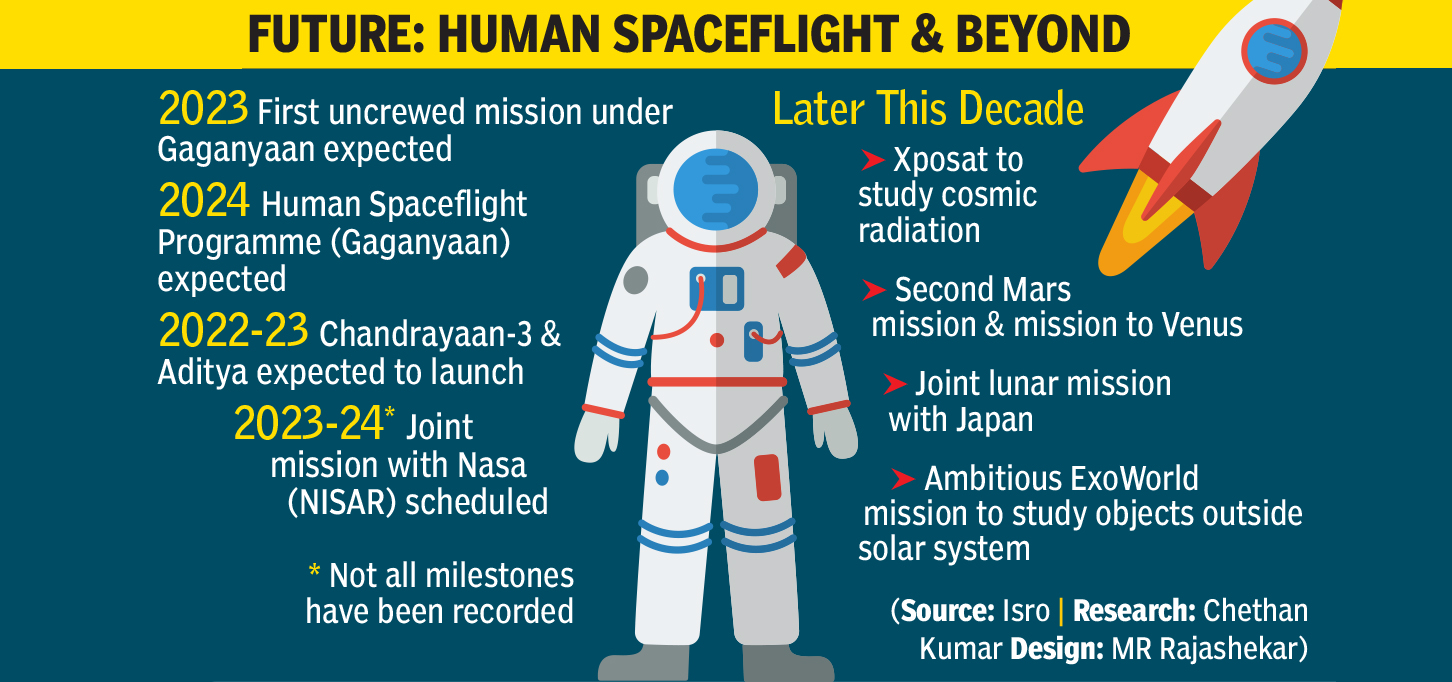

Former Isro chairman K Sivan explains: “Space tech applications have been further enhanced with a special emphasis from PM Modi. Diplomacy has grown multifold: After South Asia Satellite and a large number of MoUs to provide our remote sensing data and training of foreign personnel, we’re now creating a solar calculator for the world and will launch BhutanSat. The next logical step is enhancing space exploration (Gaganyaan and more). And as we increase our global footprints, the private sector will play a key role.”

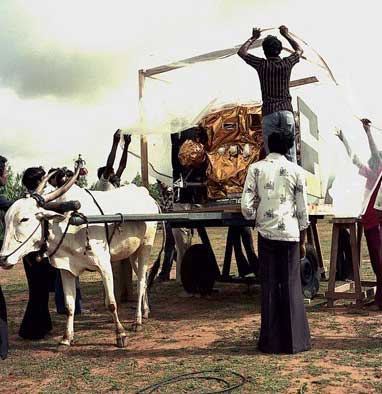

But when did the journey begin? Space research activities started in 1962 with the creation of Indian National Committee for Space Research (INCOSPAR), which enabled the setting up of Thumba Equatorial Rocket Launching Station (TERLS) in Thiruvananthapuram. After a series of sounding rocket launches and initial development of advanced technologies, India officially formed Isro on August 15, 1969.

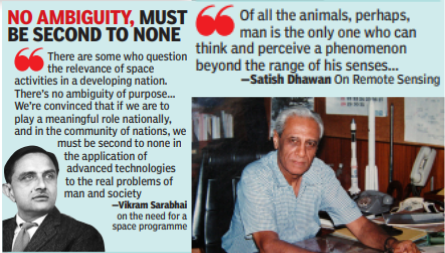

K Radhakrishnan, during whose chairmanship Isro launched MOM, says: “Our space programme can be divided into three phases — 1962 to 1982, 1983 to 2002 and post 2003. The initial phase had space science as the driver, and then came a phase that saw us taking up three major directions: space applications, satellite development and rocket development. Here we had great clarity in the vision laid down by Vikram Sarabhai. From there, we’ve grown leaps and achieved many national objectives while also exploring space through missions like Chandrayaan, MOM, Astrosat, IRNSS (regional navigation satellite system) etc.”

With more launches, operationalisation of PSLV and self-reliance in several areas, Isro, in 1990s, began looking at commercial prospects and big-ticket science missions. The agency has managed to, in the past decade or so, put into orbit nearly 320 foreign satellites, earning several million dollars.

Among its science missions are two lunar orbiters, one Mars orbiter, space telescope (Astrosat), while a third lunar mission, a maiden solar mission and a human spaceflight mission are in the pipeline.

The programme has also been lucky to have a galaxy of good scientists to-date and a string of visionary leaders — including Vikram Sarabhai, Satish Dhawan, UR Rao and MGK Menon in the early years. In recent years, Madhavan Nair, M Annadurai, S Arunan, S Somnath, Unnikrishnan Nair, TK Anuradha, Ritu Kadidal and M Vanita, among others, have handled complex missions.

Their contributions over the decades have propelled India into an elite club of nations today. From seeking foreign help for launches, India is able to rub shoulders with the best in the business. One example is the Nasa-Isro Synthetic Aperture Radar (Nisar) project, in which India is an equal partner.Also in the offing are projects with Japan (Moon), Nasa (Mars) and Isro’s own vision to explore the Sun, Venus and putting in place its own space station.