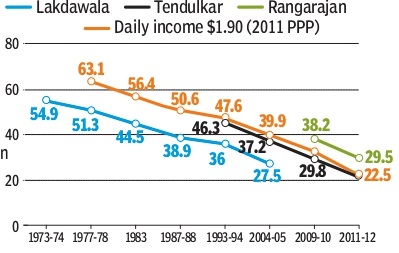

While the existence of different poverty lines makes it difficult to assess the true number of poor people in India, all lines point to reduction in poverty, writes Atul Thakur

Trend of falling poverty

India’s national line (Tendulkar) shows poverty reduced by 7.9%-points between 2009-10 and 2011-12, the last year for which data is available. The proposed Rangarajan line also shows 8.7%-point poverty reduction in this period, but estimates a higher number of poor than the Tendulkar line.

A poverty measure based on income alone ignores other factors like education and health that keep a person trapped in poverty. That’s why poverty is now also measured with a multidimensional approach factoring in health, education and general quality of life. The level of multidimensional poverty in India has been decreasing, although it is much higher than income poverty.

Other poverty indicators linked to general level of food intake – such as malnourishment and wasting in children – don’t reflect reduction estimated with poverty lines. For example, the proportion of stunted children is higher than the proportion of poor in the country. So, poverty lines are either undercounting the poor or are dynamic – meaning people escape poverty and then fall back because of a possible spike in expenses or income loss.

Planning Commission Working Group, 1962The first attempt to estimate poverty was based on nutritional intake. It identified the poor as people with per capita monthly expenditure of less than Rs 20 in rural areas and Rs 25 in urban areas at 1960-61 prices.

Y K Alagh Task Force, 1977This line was also linked to food intake (2,400 kcal/person in rural areas and 2,100 kcal/person in urban areas), based on the NSSO household consumption data, 1973-74. It was assumed that the state would provide education and healthcare.

D T Lakdawala Expert Group, 1989 The Alagh line was criticised for ignoring state-wide price differential and inflation, and assuming a fixed consumption basket over time. Lakdawala disaggregated national poverty lines into state-specific ones.

Tendulkar Expert Group, 2005The Lakdawala line was criticised for being too low. Also, liberalisation had increased household expenditure on health and education. The Tendulkar line drawn to address these issues was criticised for the same reason. The Rangarajan Committee formed in 2012 submitted a report in 2014,but a decision on it is pending.

International poverty lineThe international poverty line – daily income of $1.9 in 2011 purchasing power parity (PPP) terms – is derived from national poverty lines of 15 poorest countries, and criticised for being too low for the rest of the world. It was conceived in the 1990s when 60% of the global population lived in low-income countries. In 2018, the World Bank added two more poverty lines – PPP $3.20 a day for lowermiddle- income countries and PPP $5.50 a day for countries with higher incomes.